"Pictures (and stories)-in-Stone"; Nachalot neighborhood, Jerusalem

Start point:The Chords Bridge

Finish Point: Ammunition Hill

Section Length: approximately 8 Km

Elevation

Starting point: 800 m

End point: 850 m

Lowest point: 800 m

Trail sign: Blue

Section Map

For reasons best understood by Google, unlike the Israel Trail, Google has not as yet marked the Jerusalem Trail on its maps.

However, when Google disappoints there are other alternatives. (Click on the + sign in the picture to expand the map).

For the record…

Just like in the Israel Trail blog, this is not intended as another “From A to B” blog about the Jerusalem Trail, but rather, an opportunity for me to share with you, my readers, a personal glimpse at some of the sites, along with my perspective and thoughts about the route.

The Jerusalem Trail - Day Two Part 1:

The Multiplicity of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city of contrasts and diversity: old and new, religious and secular, historic and modern, strife and serenity. It is also a meeting place of different religions, ethnicities, and cultures. Our second day on the Jerusalem Trail gives us a glimpse of all these features and provides us with some of the spice, color, and flavor of what makes Jerusalem so unique.

The Chords Bridge

Today’s hike starts off at Santiago Calatrava’s Chords Bridge, which certainly falls under the heading of modern. The cable-stayed structure, alternately referred to as the Bridge of Strings or the Jerusalem Light Rail Bridge, was built to enable Jerusalem’s sleek light rail to bypass the busy city entrance. The bridge opened for use in 2011 and includes a pedestrian walkway.

We cross the bridge from Kiryat Moshe, a neighborhood at the entrance to town, and find cyclists riding there as well. The bridge lets us off on a wide boulevard between the end of Yaffo Steet (across from the bustling central bus station) and Shazar Boulevard (opposite the International Conference Center - Binyanei Hauma). Thousands of people pass through here daily as they wait for or descend from the light rail here, or hurry across to the bus station or the many shops that surround it, or scurry towards the many bus stops that line Shazar Boulevard.

Yaffo Street ...

... originally called Yaffo Road, is one of Jerusalem’s oldest and longest thoroughfares. It begins its route at the Old City’s Yaffo Gate and extends west through the busy downtown area until it exits the city and continues on to Tel Aviv and the ancient port city of Yaffo (Jaffa).

Although most of the original buildings here were razed to make way for the new, one can still catch glimpses of some small buildings remaining from an earlier age. Old or new, all the buildings in Jerusalem are built with Jerusalem stone, in any of its various forms (rough, pebbled, polished) and colors (white, beige, or a reddish-beige hue).

We turn to leave Yaffo behind us, but we will meet up with the street again further east.

A Bare-Boned Lady Liberty

For now, we head across the wide walkway to Shazar, then cross the multi-lane street to traverse one of Jerusalem’s newest neighborhoods, the high-rise Kiryat HaLeom (National Precinct) complex. As we wind our way through the streets, we come across a bare-boned, blue Lady Liberty, much smaller and hungrier-looking than her older, green sister in New York.

A bit further and we’re on Yitzhak Rabin Street, across from the lower end of the Supreme Court building. To our right, the road passes the Cinema City mall and leads up towards the Government Complex. We, however, turn our backs on these modern structures and head downhill to Agrippas Street.

The street serves as the southern border of Jerusalem’s Mahane Yehuda market and is busy throughout the day with both vehicular and pedestrian traffic.

Nachlaot

However, after passing only a few interesting shops and street art, we turn to the right to an area known as Nachlaot. Nachlaot is actually made up of several small neighborhoods built in the early days of Jewish settlement outside the Old City and up to the early 1930s. Even though this area lies in the center of town surrounded by modern buildings, it provides a breath of quiet and a hint of what the past was like.

The first neighborhoods built in this area were Even Yisrael and Mishkenot Yisrael. However, due to monetary problems and housing issues, only 44 of the proposed 144 apartments were built. The local council turned to the noted British Jewish philanthropist, Sir Moses (Moshe) Haim Montefiore (1784-1885) who in 1860 had helped found Mishekenot Shaanim, the first residential settlement outside Jerusalem’s Old City.

Montefiore not only agreed to their request, but also set out to build a similar neighborhood for Sephardi residents. In his honor, the Ashkenazi neighborhood was renamed “Mazkeret Moshe,” and the new Sephardi neighborhood was named “Ohel Moshe.” (The much-more-recent Kiryat Moshe neighborhood at the entrance to town is also named for Montefiore.)

Sir Moses (Moshe) Haim Montefiore

Montefiore was born into an Italian-Jewish Sephardi family. Although he himself was born in Italy while his parents were there on a business trip in 1784, his grandfather had settled in London in 1740. Montefiore worked in several different businesses, including a brokerage firm which he operated with his brother. He later became business partners with his wife’s brother-in-law, the banker Nathan Mayer Rothschild. Montefiore retired in 1820, thereafter spending his time and devoting his wealth to society and worthy causes. He became governor of Christ’s Hospital in London in 1836, was elected Sheriff of London in 1837, and was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1838. The philanthropist was also active in Jewish causes.

In 1827, Montefiore visited the Holy Land, and returned a strictly observant Jew. He served as the president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews for a period of 39 years (1835-1874), was active in synagogue, and took up the plight of persecuted minorities abroad, especially that of the Jews. He travelled to the sultan of the Ottoman Empire in 1840 to release ten Damascus Jews arrested after a blood libel, interceded with the Catholic Church in Rome to free a Jewish youth allegedly baptized by a Catholic servant and met with the czar in Russia in 1846 to intercede on behalf of the Jewish population there.

Further missions to Morocco and Romania and a second visit to Russia—along with his active promotion of Jewish business, education, health and wellbeing throughout the Middle East—turned him into a folk hero among the oppressed Jews in those portions of the world. His humanitarian activity on behalf of the Jewish people and others (Montefiore had been instrumental in the fight to abolish slavery throughout the British Empire) also earned him a baronetcy.

Montefiore had a strong interest in the Holy Land and travelled there by carriage and ship seven times. In additional to his work in Jerusalem, he purchased an orchard near Jaffa in order to set up an agricultural school there, and helped fund several agricultural colonies. In Jerusalem, he not only helped build the three neighborhoods mentioned previously, but also encouraged poor families to move there, despite the the very real threat of bandits. He built a windmill to provide cheap flour, and established a textile factory and a printing press to help provide jobs and build a self-supporting Jewish community. The windmill was later turned into a museum which housed Montefiore’s carriage until the wooden coach was destroyed in a fire.

It should come as no wonder that “Sir” Montefiore was affectionately referred to in Jewish Palestine and even today as “HaSar” (the lord/noble). In tribute to Montefiore’s contribution to the Yishuv (Jewish community in Palestine), the Bank of Israel used the “Sar’s”likeness on the ten lira (later 1 shekel) bill. Till today, his mythic status and the affection people had for him is commemorated in the song performed by Yehoram Gaon, “HaSar Moshe Montefiore.”

Sir Moses Montefiore

השר משה מונטיפיורי

Originally performed by Yehoram Gaon

Lyrics: Haim Hefer

Music: Dov (Dubi) Zeltzer

במקור מבוצע על ידי:

יהורם גאון

מילים:

חיים חפרי

לחן:

דובי זלצר

When Sir Montefiore was 80 years old

The white angels came to his home,

Stood over his bed, and said:

"The Holy One, Blessed Be He, Wants you by Him."

וכשהיה השר מונטיפיורי בן שמונים

אז באו לביתו המלאכים הלבנים

עמדו על מיטתו וכך אמרו אליו:

"הקדוש ברוך הוא רוצה אותך אליו"

And precisely like this Sir Montefiore responded:

"Forgive me, gentlemen, but I'm really busy,

Because, worldwide, our brethren are beset with many troubles.

There's a pogrom in Russia, how can I not go to them?

For who, if not me, will help everyone here?

וכך ענה השר מונטיפיורי בדיוק:

"סלחו לי רבותי, אך באמת אני עסוק

כי יש הרבה צרות לאחינו בעולם

הנה פוגרום ברוסיה, איך לא אבוא אצלם?

כי מי אם לא אני יעזור פה לכולם?"

Refrain -

And he went into his carriage, and said "Diyo!" (Giddyap) to the horses

With a discreet act of charity here and a donation there,

Here a pinch on the cheek or a loving caress.

And all the Jews felt happiness and pride.

All honor to the lord, all honor to the lord!

פזמון חוזר -

והוא עלה למרכבה ו"דיו" לסוסים אמר

ופה מתן בסתר ושמה נדבה

פה צביטה בלחי או ליטוף של אהבה

ולכל היהודים שמחה וגאווה

וכל הכבוד לשר, וכל הכבוד לשר!

And when Sir Montefiore was 90

They told him: "Arise, they're asking for you up above."

The lord asked them, "Tell me, how can I?

How will the blood libel in Damascus be called off?

וכשהיה השר מונטיפיורי בן תשעים

אמרו לו: "תעלה, כי שם למעלה מבקשים"

שאל אותם השר: "הגידו איך אוכל?

איך עלילת הדם בדמשק תבוטל?

Someone must go to the despicable Pasha to say:

"Shame on you! How is such a thing allowed!

And if someone must slip him some bakshish,*

Some large gift, but one that no one will notice?

Who, if not I, will give it to the Turk?

הלא צריך ללכת לפחה הנבזה,

ל'גיד לו: תתבייש ואיך מרשים דבר כזה

ואם צריך לשים לו ביד איזה בקשיש

מן מתנה גדולה, אך שאיש בה לא ירגיש

אז מי אם לא אני לתורכי את זה יגיש?"

Refrain -

And he went into his carriage, ...

פזמון חוזר -

והוא עלה למרכבה...

And when Sir Montefiore was 100

He said: "Enough already, my soul is satisfied.

Millions of liras, franks and bishlik** have been spent

But for the Jews, this is never enough."

וכשהיה השר מונטיפיורי בן מאה

אמר: "מספיק לי כבר, הנשמה שלי שבעה

הלכו מליונים לירות ופרנקים ובישליק

אבל ליהודים זה אף פעם לא מספיק"

They said to him, "Your honor, just come and look

Another room must be built for Rachel's Tomb,

The Western Wall must be made higher,

More Jews must be brought to Nevei She'ananim,

And who, if not you, my beloved master…?"

אמרו לו: "כבודו, רק יבוא ויסתכל

צריך לבנות עוד חדר לקבר של רחל

להגביה ת'כותל המערבי

לנווה שאננים יהודים יש להביא

ומי אם לא אתה יא מורי, יא לבבי?"

Refrain -

And he went into his carriage, ...

פזמון חוזר -

והוא עלה למרכבה...

And when the lord was one hundred and one more year,

The angels bestowed upon him a parting kiss

And so, he closed his eyes requesting

Only a Jerusalem stone (to be laid) beneath his head.

וכשהיה השר בן מאה ועוד שנה

נִשקוהו מלאכים בנשיקה האחרונה

וכך את העיניים עצם הוא בבקשו

רק אבן ירושלמית מתחת לראשו.

Wrapped in a silk tallit, resting in his coffin

Lord Moshe completed his final journey

But there are still people ready to swear

That sometimes at night, when it's dark all around

They saw Montefiore beside his carriage…

עטוף טלית של משי ונח בתוך ארון

גמר השר משה את מסעו האחרון

אך יש עוד אנשים המוכנים להיִשבע

שלפעמים בלילה כשחושך בסביבה

ראו את מונטיפיורי על יד המרכבה...

Refrain -

And he went into his carriage, ...

פזמון חוזר -

והוא עלה למרכבה...

* Bakshish - a bribe

** Bishlik - a small Turkish coin

Translated to English by Malka Tischler of Brooklyn, NY, USA (edited by Mirel Bodner Abeles)

Synagogues in Nachlaot

Ohel Moshe & Mizkeret Moshe

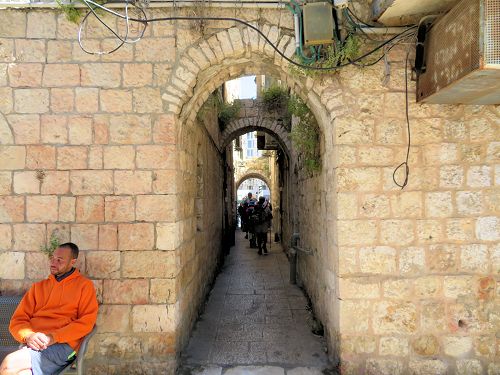

Ohel Moshe and Mizkeret Moshe were built as courtyard communities. An arched entrance led into the neighborhood of narrow streets and roomy squares. Small homes were built, trees were planted, and central courtyards were constructed with a water cistern to provide water for the neighborhood. The charter also called for the building of synagogues and set the form of prayers to be used in them.

Over time, people added extensions to the units: an extra room, a second floor. More synagogues were added, and stories and legends grew around the places and families.

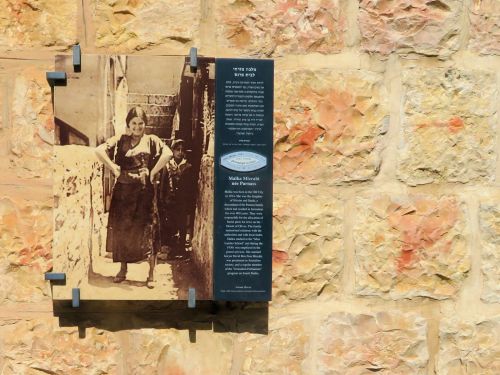

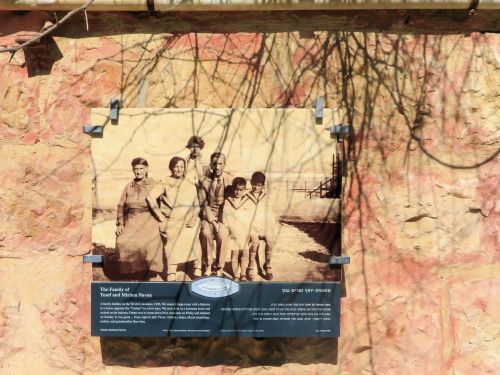

“Pictures in Stone”

Now, several of the buildings carry plaques, as part of the “Pictures in Stone” project, which bear pictures and short histories of the families who lived in the buildings.

Descendants of many of the families who lived there and in the other old neighborhoods that merged into today’s Nahlaot have influenced Israeli arts and politics till today. Among the many illustrious descendants one can find two presidents— Yitzchak Navon (fifth president, who actually grew up in the neighborhood and wrote

As we exit the narrow alleyways of Nachlaot, we emerge back onto the colorful, noisy Agrippas Street, and the famed Mahane Yehuda Market (Shuk Mahane Yehuda), often referred to in Jerusalem simply as The Shuk (The Market).

Shuk Mahane Yehuda

This largely open-air market takes its name from the Mahane Yehuda neighborhood that it borders upon. " In the late nineteenth century, Arab merchants and villagers would come to sell their goods to the people living outside the Old City. They set up shop on an empty lot that lay between the Mahane Yehuda and Beit Ya’akov neighborhoods. Under Turkish rule, the market—originally called the Beit Ya’akov market—grew and expanded haphazardly and without much direction. However, in the first decade of the British Mandate, the streets were cleaned up and permanent stalls were built. It is at that time the market was renamed for the larger Mahane Yehuda neighborhood.

In 1931, the market was extended to the west to accommodate more merchants who had been selling from temporary wooden stalls. It is referred to as the Iraqi Market, as most of the traders there were of Iraqi descent.

Nowadays, the vibrant market is still full of color, smells and sound. One can find almost everything there, from an array of colorful stacks of fruits and vegetables, dried fruits and nuts, fragrant spices and herbs (so hard to walk by, sniff the delightful aroma, without being lured by the smell to buy even spices that one doesn’t necessarily need…), fish, meat, textiles, Judaica, candies, baked goods, and what not! Added to the colors and smells are the voices of the merchants hawking their wares in different accents and tones. Some of the trades people try to entice you with tasty tidbits of halvah and sweets, others with good-natured joking, and still others by calling out irresistible prices.

More recently, many boutique stores, cafés, restaurants, and pubs have opened in the Shuk, so that the area now has a dynamic night scene as well. And then there is the magnificent wall art! No wonder the Shuk is a major attraction for tourists and locals alike. With its rich ethnic diversity, it serves as a true microcosm, a place where one can find Arab locals and tourists, Jews from different ethnic groups, tourists from around the globe, people of different religions and from different walks of life, secular and religious, young and old.

As we leave the Shuk and head back towards Agrippas Street, the sounds of Mahane Yehuda are gradually replaced by the sounds of traffic. Yet the Shuk lingers with us, losing some of its color as we progress downhill towards the center of town.

The Old Knesset

Our steps now lead us to King George Street and the Froumine building (alternatively Frumin House), now generally referred to as the Old Knesset. The original plans for the building called for a six-story structure that would serve as a residence with a bank and other businesses on street level. However, the outbreak of the War of Independence halted construction with only three stories completed.

The Provisional State Council and the first Knesset (Israeli Parliament) initially met in several different locations in Tel Aviv. Once the volatile situation in Jerusalem settled in 1949, the Knesset officially moved to Jerusalem, the country’s capitol. The first Knesset sessions in Jerusalem were held in the Jewish Agency building, while the government searched for a more permanent solution. The government eventually purchased the unfinished Froumine House, which seemed ideal for the purpose.

Frumin House served as home to the Knesset from 1950—1966, at which point the Knesset moved to its present location, further south, away from the center of town. Until 2014, the building housed various government bodies: first the Ministry of Tourism, later the Ministry of Religious Services. Frumin House is now undergoing construction to renovate the outer walls and reconstruct the Knesset plenum for the building’s reopening as the “Old Knesset Museum.” In the meanwhile, the building is blocked off by large boards covered with pictures and articles related to the early years of the Knesset.

The German Compound

We cross King George Street and proceed down Hillel Street, which runs more or less parallel to Ben Yehuda Street. Ben Yehuda and Yaffo make up the two legs of the downtown triangle, which has King George Street as its base. The apex of the triangle is at Zion Square. This area is considered the true “center” of town and draws tourists and locals alike.

Here on Hillel Street, a building on the left draws our attention. Constructed in 1886 for a German Catholic institution—then part of a German compound in the city—the building is now the site of the Umberto Nahon Museum of Italian Jewish Art. The museum has a collection of artifacts relating to Jewish life in Italy from the Renaissance period up until modern times. The most popular exhibit is the magnificent hall where the interior of the Conegliano Synagogue was rebuilt after being shipped from Italy to Israel in the 1950s. The reconstructed synagogue hosts prayer services for the local Jewish-Italian community. However, there is no time to visit museums; that must be saved for another day.

Just a bit further and we’re in Nachalat Shiva.

Nachalat Shiva

Founded in 1869, Nachalat Shiva, the third neighborhood built outside Jerusalem’s old city walls, is the oldest of the Nachlaot neighborhoods. The “shiva” (seven) in the courtyard neighborhood’s name is in reference to the original seven scions of old Jerusalem families who set up the cooperative endeavor: Yehoshua Yelling, Michel HaChohen, Binyamain Salant, Haim HaLevi, Aryeh Leib Horowitz , Yosef Rivlin and Yoel Moshe Solomon. There was a dispute between the latter two as to who had originated the idea for the neighborhood, but their names continue to reappear among those active in the building of other neighborhoods. Yoel Moshe Solomon was even commemorated in a popular song* in reference to his part in the founding of Petach Tikva. But that’s another story.

* Link to Arik Einstein singing the song on YouTube

Because of the dangers inherent in living outside the city walls, the site was chosen for its proximity to the Russian Compound, which had been built a few years earlier. Unlike the other neighborhoods, Nahalat Shiva was built by locals, without outside help. The seven families pooled their funds and held a lottery to determine the order in which the lots were to be chosen and homes built. Rivlin was the lucky one who drew first rights.

In 1872, Yosef Yitzhak "Yoshya" Rivlin (forefather of Reuven "Ruvi" Rivlin the 10th and current President of Israel) invited more families to leave the overcrowded and unsanitary conditions in the Old City and move to the new neighborhood. By 1875, fifty families were already living there.

The year 1873 saw a number of new additions. The families built the Nachlat Yaakov Synagogue, which till today claims to be the first synagogue built outside the old city walls.

In addition to the residences and synagogue, the neighborhood started two businesses: a dairy with cows imported from Holland and a carriage service to Yaffo Gate.

Today, the neighborhood is primarily known for its pedestrian walkways, colorful shops, and sidewalk cafés. In the evening, the area attracts visitors to its restaurants and pubs.

On our walk we encounter the names of the founders on various sign posts. Like in the other early neighborhoods, evidence of the Orthodox nature of the original residents can be found in the abundance of synagogues to be found, often one right next to the other.

Walking down the main road, cafés give way to shops as we approach Zion Square and Yaffo Street.

Yaffo Street

The closing off of downtown Yaffo Street to all traffic but the light rail has changed the nature of the street, so that sidewalk cafés have now joined the many shops more in keeping with one’s one idea of a downtown shopping mecca. Amid the hustle and bustle one can hear snatches of conversation in different languages from the many tourists and local olim mixed in with the Hebrew of the locals. This busy corner of Jerusalem is a wonderful spot for people watching.

In fact, we’re stopped by a group of locals seated at an outside table. They’re curious about us; I guess they are not used to seeing people in hiking gear in downtown Jerusalem.

Turning right, we head down Yaffo Street. Behind the buildings on the opposite side of the road lies the Russian Compound, built largely between 1860 and 1864 to accommodate the large numbers of Russian pilgrims who came to Jerusalem at that time.

As always in Jerusalem, past and present intertwine and reminders of different periods blend together, as we go from the 1860s to the present, and then back to the Mandate years, somewhere in between.

“Bevingrad” and Operation Pitchfork

Once in control the British commandeered the complex with its many historic and interesting buildings. Later, they fortified the area along with other important nearby British centers in a enclave that the citizens of the time cynically called “Bevingrad”. When the British departed, the Hagana succeeded in taking over the area as part of Operation Pitchfork. But we pass the Russian Complex by, as it’s not on our itinerary today.

That is another story (link inactive now)

Before us is the triangular Generali Building, where the street splits into Yaffo Street on the building’s left, and Shlomtzion HaMalka Street on its right. Taking the left fork, we pass the Generali Building and the wide row of stairs leadings down to the lower street. Right past these stairs is is a wide rectangular building built by the British in 1934 to serve as both post office and telephone exchange and which also housed part of the staff of the Palestine Post.

The Central Post Office

Where Art and Service Coexist

The structure still serves as the city’s central post office. We enter the building to view a huge mural painted in 1972 at the initiative of Shimon Peres, then Communications Minister and later 9th president of Israel. The mural by Bulgarian-born Israeli sculptor, painter, and muralist Avraham Ofek fills the wall behind the tellers in the main hall.

Ofek (1935-1990) thought art should be taken out of museums and exhibited in public for all to enjoy. He believed in art for society, not just for museum-goers and collectors.

The central post office’s mural is one of several Ofek works in public places throughout Israel. The most famous among them are the murals in Beit Haam, Kfar Uria; at the Stone and Agron Schools, Jerusalem; the “Return to Zion ” at the Tel Aviv University Library, Tel Aviv; the “Binding of Isaac,” sculpture in Safra Square, Jerusalem; and the mural, “Israel,- a Shattered Dream” at Haifa University, Haifa.

The mural in the central post office is certainly magnificent. It draws the eyes and is well worth the visit, but I wonder if the bored people waiting their turn find it any comfort.

Safra Square

Safra Square, named for the parents of Lebanese-born Brazilian banker and philanthropist Edmond J. Safra, was built in response to the need for improved municipal functioning. The square is actually a triangle with its point at Tzahal Square, the location of the original municipality compound. The rounded part of the original municipal building faces Yaffo Gate and the old city walls, and once housed a branch of Barclays Bank.

Since the building of the former municipality compound by the British in 1930, the city had grown considerably in size and diversity, providing new challenges. The number of municipal offices grew as well, and were scattered across the city, hampering efficiency. To rectify the situation, the municipality decided to build a new compound around the original site on the seam between East and West Jerusalem, symbolizing the city’s ties to the past as well as its aim to serve all its residents.

Bordering the Russian Compound, the site contained ten 19th century buildings of historical and cultural importance which required restoration and preservation. Architects worked on a design for the three new buildings and the overall compound so that they would come together to form a pleasing whole. Construction, which began in 1988, was completed in 1993.

The complex is accessible from many different directions. The approach from Yaffo Street is via Palm Plaza, so named for the 48 palm trees that line the steps leading from the main street to the complex.

Among the many permanent works of art located at the square are a few sculptures of lions, symbol of Judah and of Jerusalem, and works by noted artists such as sculptors Roy Lichtenstein and Avraham Ofek and Armenian ceramist Arman Darian.

The large, central square in the middle of the compound is used to host many different events, from book fairs to street ball, and during the Sukkot (Tabernacles) holiday, holds Jerusalem’s largest sukka.

The visitor’s center in the municipality has a porch from which Jerusalem can be viewed from above. The wonderful panorama calls to me as a photographer, and my camera clicks away.

Afterwards we visit the center’s mini-Jerusalem room, where we can see a huge model of the entire modern-day city. There are also displays of the site’s history, from the days of the Ottoman Empire up to the present.

We exit the municipal compound at Tzahal (IDF) Square, where a Jerusalem lion sculpture stands guard.

Musrara

To our left is Shivtei Yisrael (Tribes of Israel) Street, which runs along the eastern side of Safra Square. This southern section of the street is part of the Morasha (Musrara) neighborhood. Unlike the other neighborhoods we’ve visited, Musrara was a neighborhood built by wealthy Christian Arabs in the 1890s, in the period of departure from the cramped and squalid conditions within the city walls.

Until the birth of the State of Israel, the neighborhood had a predominantly Christian Arab population, although there were some Jewish families who lived there as well. For example, the family of Reuma Weizman, wife of the seventh president of Israel, lived in the Musrara neighborhood.

In addition to the lovely private homes with impressive entrances built in the Arab style, the neighborhood also has several Christian institutions, some of which predate the neighborhood. For example, right on Shivtei Yisrael Street, we pass St. Paul’s Church, the first Arab Anglican church in the area, built in 1873. Since its renovation in 2011, it holds tours in addition to conducting its regular prayer services.

The Decline and Resurrection of Musrara

During the War of Independence, the neighborhood’s Arab residents either fled or were expelled from the area. In the early years of statehood, there was a severe housing shortage exacerbated by the influx of immigrants escaping the horrors of the Holocaust and the pogroms in Arab countries. The Ministry of Housing decided to settle immigrants, mostly from Arab countries, in the largely deserted Musrara neighborhood.

Until 1967, when the city was reunited after the Six Day War, residents were prey to daily sniper attacks from Jordanian soldiers.

Anyone with the funds to leave the neighborhood did so, and the once lovely, upscale neighborhood turned into an impoverished, neglected slum. Only in the 1980s, after the rise of political protest movements, did the local municipality invest in programming to restore the neighborhood to its former glory, which we see today.

The Italian Hospital

Continuing north, we pass the three-story, Renaissance-style Italian Hospital designed by Antonio Barluzzi, and completed in 1919. In addition to the main hospital building, the complex also included a church and a tall, square bell tower. The structure is reminiscent of various noted Italian monuments and incorporated depictions of knights from the Italian Crusades (which were removed by the British during WWII).

The stone gate was embellished with metal scrollwork portraying themes from Roman mythology. In World War 2, the complex was confiscated by the British and served as the command center of the RAF in Palestine.

Towards the end of the mandatory period, both the Jewish and Arab forces wanted control of the building in order to use the high bell tower as a strategic observation point. To this end, Jewish forces listed the building as one of the objectives in central Jerusalem during Mivtza Kilshon (Operation Pitchfork). A cook who worked at the complex notified the Hagana of the precise departure time of the British, enabling the Hagana forces to occupy the building without a fight.

After statehood, Israel purchased the property from the Italians, and installed the Ministry of Education in the buildings there. The later addition of a new building in the Italian complex provided more office space, so that the compound continues to serve the needs of the ministry.

Meah Shearim and Beit Yisrael

We continue to meander down Shivtei Yisrael, passing Meah Shearim. The street continues as Beit Yisrael Street when it enters the neighborhood of that same name.

Beit Yisrael was built in the 1880s as a suburb of Meah Shearim, for people who could not afford the price of housing there. Both of these neighborhoods have retained their original religious, Jewish atmosphere and are home to an ultra Orthodox population.

People in Chassidic dress scurry by, the men looking down so as not to catch sight of the women who might be dressed immodestly.

We take a short break in the shade before continuing on to the last part of the day.

The Italian Hospital

What irony and quirk of fate!

A Catholic Christian structure now houses the Israeli Ministry of Education.